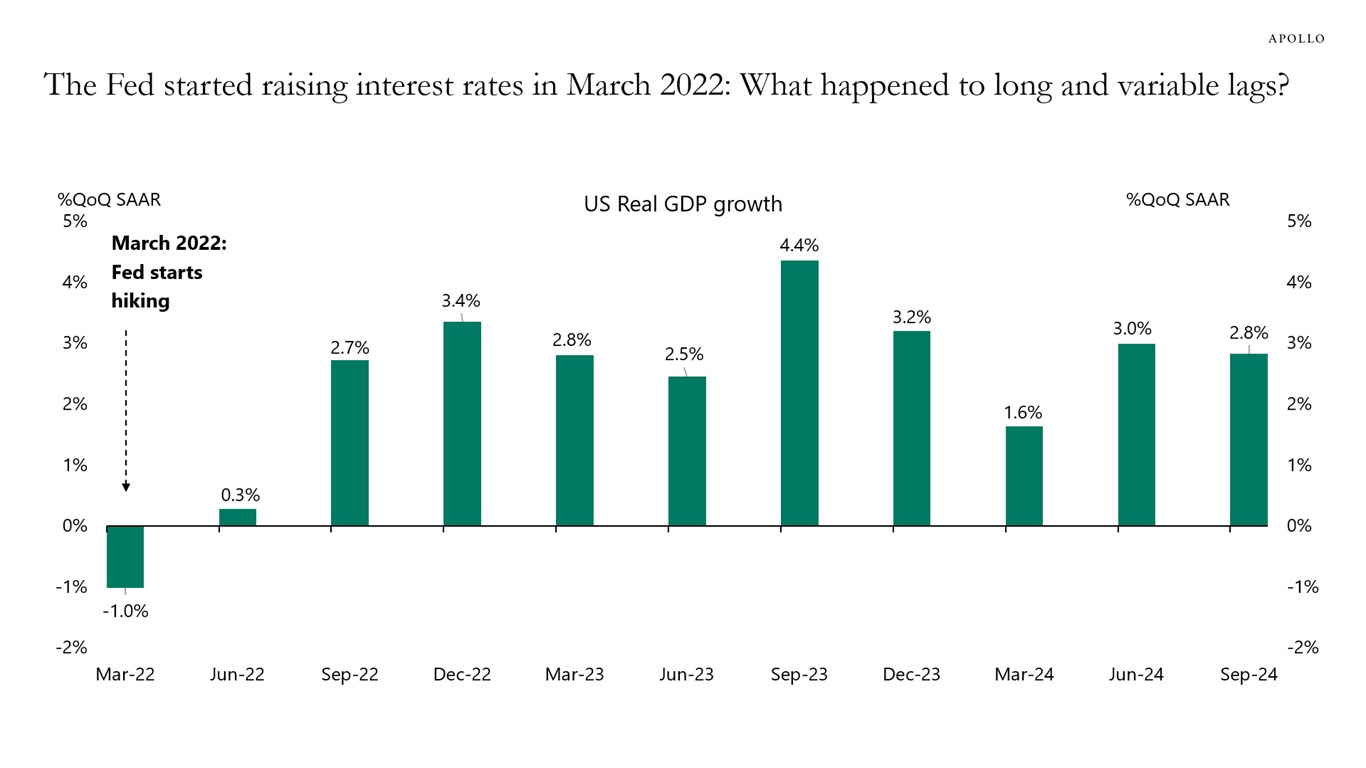

When the Fed started raising interest rates in March 2022, a lot of Fed speeches and market conversations focused on the long and variable lags of monetary policy, i.e., the time it takes before Fed hikes begin to slow down the economy.

Traditional impulse-response functions in VAR models and the Fed’s own model of the US economy, FRBUS, suggest that it should take 12 to 18 months before tighter monetary policy begins to slow the economy down.

However, it has been 30 months since the Fed started raising interest rates, and we have still not seen any sign of a slowdown. This week, we got GDP growth for the third quarter, and it came in at 2.8%. And the Atlanta Fed’s GDP estimate for fourth quarter GDP is 2.3%, above the CBO’s 2% estimate for long-run growth.

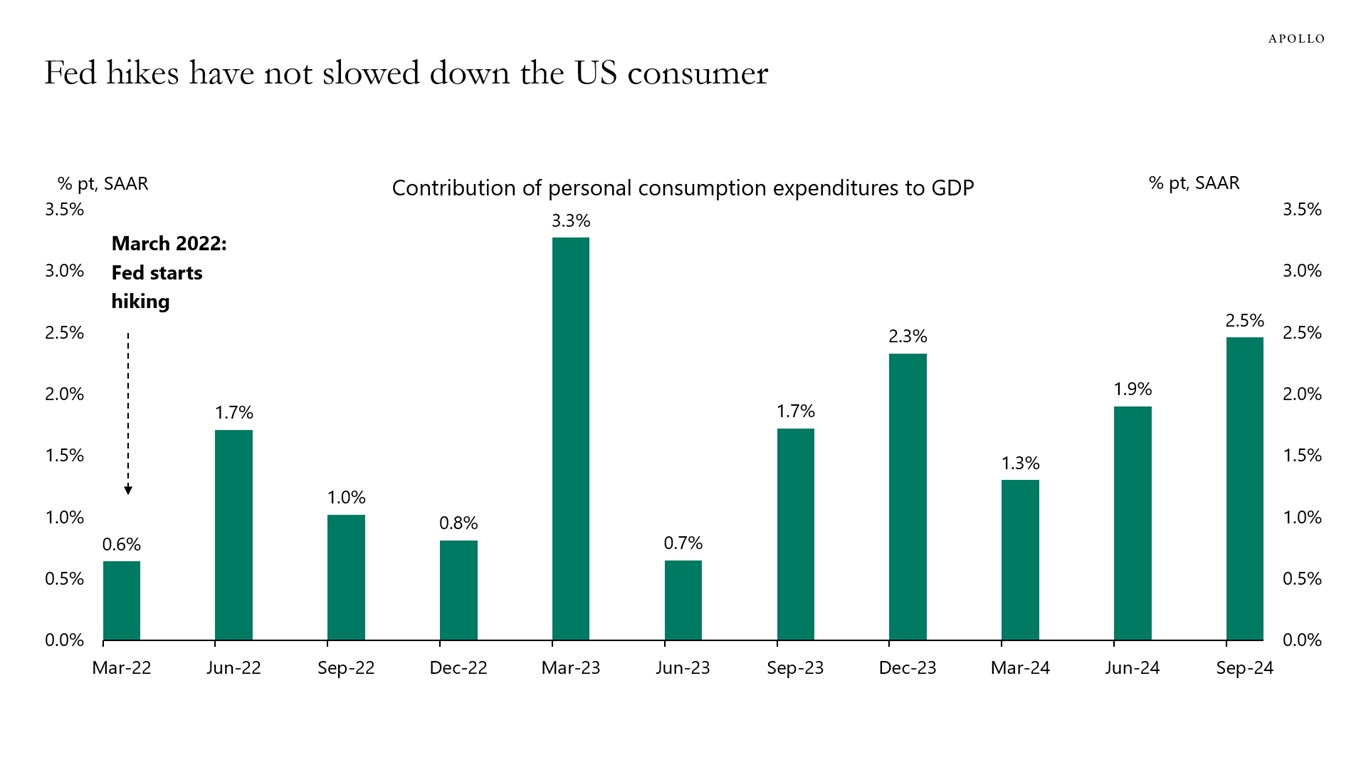

This is the key issue across the S&P 500, credit, FX, and private markets: What happened to long and variable lags? Why is GDP growth still above potential, and why did Fed hikes not slow down consumer spending and capex spending the way the textbook would have predicted?

There are three reasons:

First, the US economy has been less sensitive to interest rate increases because consumers and firms locked in low interest rates during the pandemic.

Second, the US economy continues to experience a big structural boom in AI and data centers.

Third, fiscal policy is easy with a 6% budget deficit, driven by the CHIPS Act, the IRA, the Infrastructure Act, and defense spending.

These tailwinds combined have offset the mildly negative impact of Fed hikes on highly leveraged consumers and firms.

In addition, these three tailwinds are unique to the US, which is why the business cycle is strong in the US and weak in the rest of the world.

With the Fed now cutting rates and these three tailwinds still in place, the outlook for the US economy continues to be positive.

Our latest chart book with daily and weekly indicators for the US economy is available here.